Introduction

Welcome back to Voices from the Field, the article series where our Materia editors conduct interviews with prominent researchers and practitioners spanning the fields of conservation, conservation science and art history. Through recording these discussions and ideas, we aim to promote dialogue surrounding the topic of technical art history. In past issues, these dialogues have focused specifically on themes such as interdisciplinary collaboration, theoretical frameworks and art historical connections, while also addressing the future of art technical analysis as an area of research.

In this latest edition of our Voices series our interviewees Jørgen Wadum and Sally Woodcock reflect on their careers and expertise within technical art history. Through their backgrounds in conservation, archival research and the integrated study of art objects, they offer insights into the breadth and diversity of their chosen field of research. In particular, our editors encouraged our interviewees to consider more fully the unique role of the conservation practitioner when it comes to the empirical examination of artworks, while also reflecting on the importance of consulting art technological source materials as a complement to scientific analysis. In addition, we touched upon various subjects and issues facing the continued development of the field, such as the establishment of open source digital databases, the application of art theoretical frameworks, and also education within art history and practical conservation. As always, we hope you enjoy these discussions and we also welcome [personal reflections and comments from our readership, so please write to us at info@materiajournal.com

Interviewees

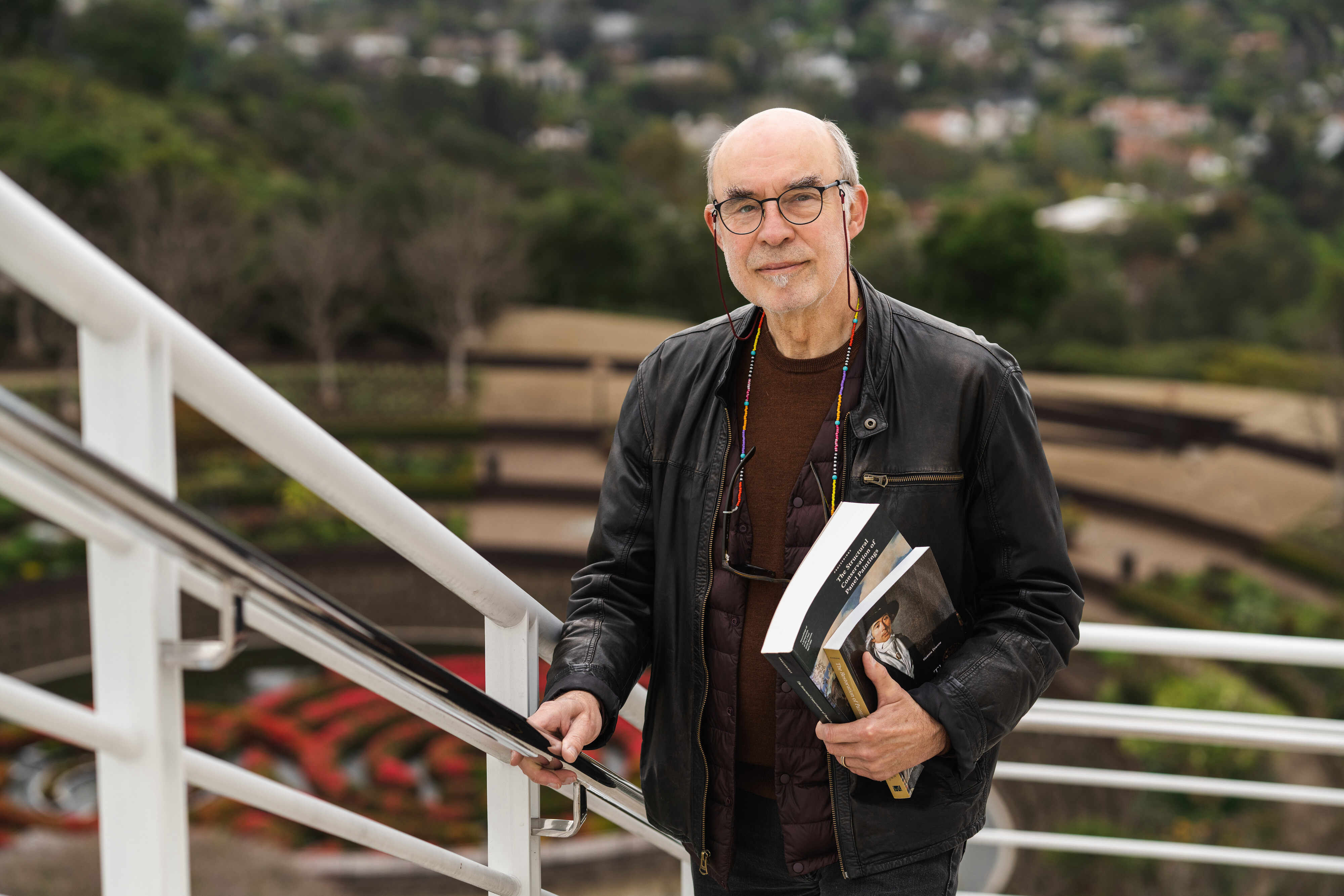

Jørgen Wadum is Director of Wadum Art Technological Studies, a Specialty Advisor on Dutch and Flemish art at the Nivaagaard Collection, Nivå, and an Associate Researcher at the RKD – Netherlands Institute for Art History. Until 2020 he was Director of the Centre for Art Technological Studies and Conservation (CATS) at SMK, Copenhagen. Previously, he was a full Professor in Conservation and Restoration at the University of Amsterdam (2012–16), Director of Conservation at SMK (2005–17), and Chief Conservator at the Mauritshuis, The Hague (1990–2004). He has published and lectured extensively and internationally on a multitude of subjects related to technical art history and other issues of importance for the understanding and care of our cultural heritage. Wadum holds positions in several international organizations and committees.

Sally Woodcock is an easel paintings conservator and technical art historian. Her longstanding interest in the trade in artists’ materials in nineteenth-century Britain began at the Hamilton Kerr Institute, Cambridge, examining the papers of the Victorian artists’ colourman Charles Roberson. She is currently preparing her PhD thesis, Charles Roberson, London Colourman, and the Trade in Artists’ Materials, 1820–1939, for publication. She is also an affiliated researcher of the Hamilton Kerr Institute, contributing to research on the colourmen’s archives at the institute, as well as developing a related research project entitled The Starving Artist: The Romance and Reality of Suffering for Art in the Long, Hard Nineteenth Century. The latter combines the history of art with social and cultural history in order to illuminate the lives of the lower ranks of British nineteenth-century artists who failed to thrive in what, for others, became known as “the golden age of the living painter.”

Questions for Jørgen

Q: Starting out first as an art historian and then as a conservator, what was it that brought you to the field of technical art history specifically? Can you offer some reflections on the relationship between technical art history and practical conservation?

While studying art history, I developed a particular fondness for courses focused on various techniques, spanning engraving, architecture, and sculpture. My interest in documentation and technical art history was initially sparked during my training in the late 1970s and early 1980s under Steen Bjarnhof, a paintings conservator and head of the paintings department, and Ulla Haastrup, an art historian, both at the School of Conservation at Copenhagen’s Royal Academy of Fine Arts.

Subsequent studies in technical art history, coupled with a rigorous analysis of artworks to uncover their inherent values, were influenced by Thomas Bullinger (Denmark), Svein Wiik (Norway), and Ernst van de Wetering (The Netherlands). Each of these individuals brought a passionate and holistic perspective to their exploration of artistic creativity.

During my master’s thesis on the genesis of the Winter Room (1613–20) at Rosenborg Castle in Copenhagen, enlightening discussions with Mogens Bencard, former director of the Royal Collections at Rosenborg Castle, deepened my commitment to integrating my skills as a painting conservator with technical art history, both of which were always part of my approach when engaging a new treatment.1

Q: You have worked in various museum settings, from the Mauritshuis in the Hague to the Statens Museum for Kunst in Copenhagen, not to mention your involvement in the Centre for Art Technological Studies and Conservation (CATS). What are some of the main challenges you have faced in coordinating technical research between different museum departments? Do you have any advice for other researchers when it comes to interdisciplinary collaborations of this kind?

In 1990, when I began working at the Mauritshuis, there were no internal lab facilities available, nor at the other museums under our care (Kröller-Müller Museum, Rijksmuseum Twenthe, and Museum Mesdag), nor at the adjacent studio of the RBK—the Dutch state’s department of art. However, what distinguished the Netherlands was the presence of the Central Laboratory for Research on objects of Art and Science in Amsterdam, popularly known as the Central Lab. While not always deeply involved in routine examinations (which I believe are essential for uncovering unique opportunities for innovative research), the Central Lab served as a significant collaborator with Dutch museums. This was particularly crucial during the “verzelfstandiging” (privatization) of the twenty-one former state museums, including the Mauritshuis, under the Deltaplan, a rescue initiative aimed at safeguarding cultural treasures in museums, archives, monuments, and archaeological sites from physical destruction.2

In this environment, I took the initiative to coordinate research efforts, especially after Jaap Boon from the FOM Institute for Atomic and Molecular Physics (AMOLF) engaged with the Mauritshuis conservation team. Together, we established a “science lab without walls” that fostered groundbreaking scientific and technical analyses of artworks undergoing treatment, involving art historians, our team of conservators, and educators. This project coincided with the establishment in 1995 of the MOLART (Molecular Aspects of Aging in Art) project, which fundamentally changed the conservation science field. It was followed by the De Mayerne Program (2002–6), which produced more than fifteen heritage science PhDs. In this brewing environment, in 2000 Erma Hermens, currently Director of the Hamilton Kerr Institute for Easel Painting Conservation and the Conservation and Science division at the Fitzwilliam Museum, and I initiated the establishment of the journal ArtMatters – Netherlands Technical Studies in Art, a journal that after four printed volumes today exists as a platform for peer-reviewed, open-access publications within technical art history, under the title ArtMatters – International Journal for Technical Art History.

Returning to Denmark and the SMK in 2005 felt like starting afresh. There were limited lab facilities for the technical and scientific analysis of artworks and no established collaborations with similar institutions responsible for examining and preserving our diverse cultural heritage. This motivated me to engage in meetings between Mikkel Scharff and René Larsen, respectively associate professor and rector of the School of Conservation, and Jesper Stub Johnsen, head of conservation at the National Museum of Denmark. These meetings eventually led to the establishment in 2011 of the Centre for Art Technological Studies and Conservation (CATS). CATS consolidated equipment and expertise across all three institutions to advance technical research into cultural heritage objects in Denmark, thereby bolstering conservation science and technical art history. Apart from numerous research results, often in collaboration with external partners, CATS also initiated biannual technical art history conferences covering issues such as the study of fifteenth- to eighteenth-century European paintings (2012); eighteenth-century paintings and works of art on paper (2014); European visual arts, 1800–1850 (2016); trading paintings and painters’ materials, 1550–1800 (2018); and grounds in European painting, 1550–1750 (2019). All of the conference presentations were published in hard copy and as a free online PDF.3

The primary challenge in maintaining this collaborative, “without walls” approach across all stakeholders was overcoming individual reluctance to share responsibilities and enthusiasm across departments, particularly among administrators who may not have fully grasped the benefits of interinstitutional cooperation. Nevertheless, the creation of CATS has firmly positioned Denmark on the global map of conservation science and technical art history. Achieving and sustaining such an initiative demands more than full-time dedication; it requires continuous nurturing and encouragement of all involved parties.

Q: It is sometimes thought that in order to conduct technical research on paintings one must first have access to advanced analytical equipment, which is often inaccessible outside an institutional context. However, you also have extensive experience in studying panel makers’ marks and the reverse of copper supports—both of which reveal clues to the contexts of their making. Can you comment on the importance of empirical observation in art technical research, and what might be termed the “conservator’s eye?”

Franciscus Junius, in the Dutch edition of his De Schilder-konst der Oude, Begrepen in drie Boecken (Middelburg, 1641), emphasizes the necessity of “een Konst-gheleerd oogh”**—**a learned eye. Interestingly, he argues that quoting classical antiquity or other humanist sources alone is insufficient for discussing art and its values intelligently. Instead, a deep understanding of the art of painting is crucial, starting with the ability to truly observe art. This skill is fundamental for conservators, who must carefully scrutinize objects on the workbench before making decisions on treatment. Too often, crucial clues about an object’s creation are obscured, removed, or even destroyed during treatment because their significance was overlooked.

Thoroughly documenting all aspects of an object’s material condition—such as tool marks, panel maker’s marks, or stamps on the back of panels and canvases, and the construction of stretchers and cradles (which often have obscured panel marks)—provides invaluable tacit knowledge.4 This information enhances our understanding of historical crafts, organizational methods, and artistic creativity of the past. Therefore, alongside analytical and hands-on skills, a learned eye is essential in our profession.

While it may be premature to suggest that conservators should assume hermeneutic responsibilities for interpreting cultural objects as reflections of human experience on a broader scale, it is crucial to acknowledge that documenting conservation activities and observations—whether conducted individually or collaboratively with scholars in the sciences and humanities, museums, or private sectors—can yield profound insights into the creation and significance of our cultural heritage. High-tech scientific analyses can certainly augment our understanding, but it all commences with the “conservator’s eye,” as you aptly queried.

Q: In a past interview, you brought up some of the current challenges facing technical art history, such as the need for digital research infrastructures and the sharing of metadata.5 Have you seen any recent improvements on this front, or if not, do you see any ways in which this could be achieved?

Digital research infrastructures are indispensable for our ability to locate and compare similar or analogous objects and phenomena. In my recent paper at ICOM-CC 2023 in Valencia, I delved into the painting techniques of Rembrandt and his contemporaries during the 1630s–40s, primarily relying on digital images sourced from the Rembrandt Database at the RKD. This database hosts digital infrared images of tronies and portraits contributed by colleagues worldwide. However, effectively harnessing these resources to their fullest potential often demands a cultivated skill, particularly nurtured early in one’s career.

Managing the substantial volumes of data amassed on objects, artists, or locales can prove challenging, given the complexity of analyses and treatment reports generated by heritage scientists and practicing conservators. Moreover, curators and art historians increasingly incorporate technical studies into their research, yielding diverse datasets, complemented by contributions from the digital humanities. Each dataset—whether images, textual records, or analytical measurements—can underpin specific historical, art historical, cultural historical, or technological interpretations. Yet, integrating these disparate datasets, acquired in varying formats and using different equipment, remains a persistent challenge. As a result, findings are often considered in isolation rather than amalgamated.

Despite the proliferation of digital tools and databases, it is crucial to recognize that navigating traditional libraries and museum archives is also a skill. Many vital resources remain undigitized on library shelves. Furthermore, it’s essential to remember that research publications in languages other than one’s primary language may have already addressed potential research topics. Though replication within the humanities is still evolving, it’s prudent to ensure that your chosen topic hasn’t already been explored, even if not prominently visible online.6

Q: In the same interview you mentioned the development of a “New Art History” in the late twentieth century, whereby focus shifted from the material object itself towards more abstract or representational interpretations of the artwork, exemplified by analytical frameworks such as Marxism, semiotics, and deconstruction. You also reflected on the development of a new “material turn.” Do you see this as something distinct from the material turn of the 1990s, or more as a continuation? Do you see any promising developments within art theory that could help bring technical examination into the fold?

I believe interest in the materiality of our cultural heritage remains robust, captivating both the public and professionals within the heritage sector. Technical art historians have not only found fertile ground for disseminating their findings but have also kept the field of material studies vibrant as new scientific methods continue to emerge, opening fresh avenues for investigation and understanding.7

Through analyses conducted with both traditional techniques and state-of-the-art equipment, documentation and research into our cultural heritage necessitate interdisciplinary collaboration. By addressing questions related to interpretation and comprehension of artworks, we not only enhance the scholarly discourse but also contribute to a deeper appreciation and sensitivity towards museum collections through active dissemination.

It’s worth noting that the 2024 international CIHA World Congress in Lyon centered around the theme “Matter Materiality,” emphasizing the ongoing relevance of material studies in our understanding of art and cultural artifacts.8

Q: Having read the answers by your co-interviewee Sally, do you have any comments or reflections on her thoughts about technical art history as a research discipline?

It was a true delight to read Sally’s account of her incredibly valuable research into the Roberson Archive and the dissemination of the various insights extrapolated from the sources. Discovering such a rich research opportunity that can continue to engage not only oneself but also attract other researchers and the public for over thirty years is, of course, immensely rewarding.

Having experienced a similar level of engagement in various fields such as history, art history, computer science, the social sciences, and conservation, I find the opportunity to delve deeper into the history of the creation, marking, and branding of panel supports for early modern painters in the Netherlands a unique and invaluable life experience. I can only conclude that Sally and I have been extraordinarily fortunate in finding subjects that seem inexhaustible when it comes to uncovering new information for evolving contexts.

However, our success stories should be viewed against the backdrop of a severe lack of funding for the field of technical art history. Many young researchers struggle to find the resources necessary to engage in research projects, and many museums still undervalue this field, prioritizing non-sustainable traveling exhibitions driven by growing communication teams rather than exploring the histories embedded in the objects within their collections, waiting to be uncovered and shared with an eager public.

Funding bodies often perceive our research as falling between two disciplines—neither purely history, nor art history, nor conservation. Therefore, it is crucial that we raise awareness of the contributions technical art history researchers can make, not only within our proceedings and journals for our peers but also for society at large. This is especially true for cultural institutions that depend on visitors hungry for new insights into the wealth of information our heritage objects can offer after scrutiny by a technical art historian and related heritage scientists.

Questions for Sally

Q: You started your career in easel paintings conservation at the Courtauld Institute of Art. What was it that later brought you to the field of technical research, exemplified by your research on the Roberson Archive at the Hamilton Kerr Institute, as well as your more recent collaboration with the Centre for Research in the Arts, Social Sciences and Humanities (CRASSH), where your research project focuses on the concept of the “starving artist” in nineteenth-century Britain?

My work as a practising paintings conservator was interrupted almost as soon as it began. Shortly after leaving the Courtauld, while working abroad as a conservation intern, I saw a three-year research post advertised at the Hamilton Kerr Institute, generously funded by the Leverhulme Trust. As funded research was, and still is, extremely rare in our field, I felt it was an opportunity that might not come up again for some time. I was worried that by switching to research so early in my career I would be rendering myself unemployable as a practising conservator forever afterwards, but my tutor, the late Caroline Villers, both encouraged me to apply and reassured me that my conservation skills would still be there when I finished. This advice was both kind and accurate and is something I have since passed on to others expressing similar misgivings about taking career breaks of any nature.

The three years I spent researching the Roberson Archive, the papers of one of the most important manufacturers of artists’ materials in Victorian London, were fascinating and fulfilling, and provided me with a career-long research interest in British nineteenth-century artists and their materials. I was extremely fortunate in that Ian McClure, then director of the Hamilton Kerr, offered a subtle steer when needed, but also let me follow my own interests in investigating some of nineteenth-century art’s more peculiar practices and less celebrated artists, which indirectly led to my postdoctoral project on the social and material history of Victorian “starving artists.” It is a testament to the strength of the Roberson archive material that since I left the institute in 1997, not a month, and more often not a week, goes by without someone sending me a question about it. These come from students, conservators, and curators, often raising highly technical issues, as well as from members of the public who own paintings with a Roberson stamp and hope the archive can identify them. While I returned to conservation practice, both as a museum professional and an independent practitioner, this constant interaction with other researchers was instrumental in encouraging me to embark on my doctoral research on the Roberson archive, completed in 2019. It is also perhaps a testament to the collegiate and collaborative nature of the academic community Ian established at the Hamilton Kerr that I have answered these queries pro bono for almost three decades, something that has recently been recognised by my appointment at the Fitzwilliam Museum as an affiliated researcher to facilitate ongoing research.

So my career could be seen as a cautionary tale: any fool can work for nothing. It could also be regarded as patchy and uneven, without the focus of a conservator devoting their career to a single collection or remaining in an institution and rising through the ranks. It is also certainly an indictment of the lack of funding for the arts in general and technical art history in particular, with almost all of my research, including my doctoral thesis, being self-funded. However, I also feel it demonstrates the agility and flexibility of our small, specialized field—with so many areas yet to be explored—that a combination of determination, luck, and a sympathetic host has made it possible to combine practical work with a sustained research output, even while operating as a freelance conservator. Enquiries sent to me relating to the archive have not reduced in number, despite it being three decades since I first worked on it, and this continuous interest has peaked with every publication I have produced. I therefore hope that the Leverhulme Trust would be pleasantly surprised to see the extent to which their three years of funding has been made to stretch over the past thirty years and feel satisfied that their investment in what was then a rather obscure and ill-defined discipline has been repaid.

Q: Your research on the Roberson Archive offers an excellent demonstration of the significance of archival materials within art historical research. This relates not only to questions on technique and the use of artists’ materials, but also broader frameworks such as trade, availability, fiscal relationships, and artistic narratives. Can you offer some reflections on your research process, whereby you move from the technically specific information held within the archival material itself towards these broader, more encompassing art historical discussions?

When I completed my PhD, my supervisor Peter Mandler reminded me that when we first met I told him that, although my thesis concerned a business, its history and its customers, a large part of it was likely to be “all about the paint.” It actually turned out to be almost entirely “all about the people.” In part this was dictated by the nature of Roberson’s records, the firm being unusual amongst artist’s colourmen in preserving its customer accounts, giving a unique insight into the purchases, finances, geography, and material choices of a wide range of artists, both professional and amateur. It was also influenced by the fact that my thesis was examined in the history, rather than the art history, department in Cambridge because Professor Mandler, an eminent cultural historian with a wide-ranging knowledge of nineteenth-century British history, was a perfect fit for the broader context, so perceptively outlined in your question, in which I wanted to locate my research.

The Roberson archive offers material of interest to those working in many fields beyond art and its histories: social, cultural, economic, and business historians; historians of science, human geographers, genealogists, collectors, curators, and anyone owning a work of art with a Roberson stamp or label. The wide-ranging reach of this material has led to fiction writers asking me for background details for their novels, vicars researching items that decorate their churches, genealogists compiling family histories, collectors seeking to identify artists, conservators treating deteriorating paintings, art historians working on theses, catalogs, and monographs, curators staging exhibitions, and, perhaps most surprisingly, a celebrated American crime writer looking for Jack the Ripper in Roberson’s account ledgers. Roberson’s connections to a wide network of other businesses and individuals working in Victorian London’s vibrant and expanding art market mean that their account books go far beyond paint, paintings, and painters. My forthcoming monograph based on my doctoral research puts Roberson’s commercial activity into its cultural context, discussing issues of supply, fabrication, trade, consumption, and display, while also demonstrating how an appreciation of the world of objects can illuminate the society that made, used, valued, or discarded them.

As an example of how the research process can go from a specific technical detail to a broader discussion of the Victorian art world, a recent enquirer sent me an image of a Roberson label on the reverse of a painting, asking if I could tell her anything about it, but provided no further information. From names and addresses on the label and the label format, it was possible to date the canvas to within a twelve-year window using Jacob Simon’s excellent material on the National Portrait Gallery website9 and the [Index of Account Holders in the Roberson Archive, 1820–1939]{.underline}, published in 1997. The painting’s artist held an account with Roberson and died at the address given on the label, the last listed in his account. Probate records showed that he left a rather small estate, and the Roberson Index indicated that his wife opened an account after his death—probably, in common with other impoverished artists’ widows, using Roberson to sell her husband’s remaining works.10 So, even before looking at the account entry in the ledger, one small detail on the reverse of a painting identified the artist, his wife, and where they lived, and raised questions about income and social status for lower-ranked artists living in the so-called “golden age of the living painter.”11 So, there is more to be found in Charles Roberson’s account ledgers than pounds, shillings, and pence: Taken at face value, the ledgers are purely transactional, a record of what was bought, how much it cost, and who paid for it, but taken as a whole, the archive opens windows onto many aspects of nineteenth-century life, both artistic and otherwise, and there remain many unexplored avenues for others to investigate.

Q: In many ways, your research also demonstrates another important, yet perhaps not equally highlighted, aspect of art technical research—what we refer to as art technological source materials. This can include a broad variety of archival sources, such as purchase orders, ledgers, and product catalogs, as well as artists’ treatises, diaries, and notebooks. Can you discuss the interplay between written sources and scientific analysis using instrumental methods? How do the two complement each other?

The nineteenth century was a time of technical innovation in materials and, in particular, in industrial chemistry, leading to a vast increase in the range and intensity of pigments and an expansion in the choice of media and varnishes available. The people who deployed this expansive repertoire of materials also left a rich, varied, and increasingly accessible archive of technical and art historical material recording what they used and how they used it, in part because developments in reprographics encouraged an unprecedented proliferation of documentary resources that are now available to aid research. In addition, as paintings of the period start to require conservation treatment, they are beginning to be subjected to more-detailed technical examination and analysis while in the studio. Combining material from these rich documentary sources with scientific and analytical findings presents the chance to find out more about nineteenth-century works of art than those from perhaps any other period.

In the course of my own research, in addition to the Roberson archive itself, I have been reliant on a wide range of related resources, documentary, material, and virtual. These have included census returns, wills and probate records, charitable registers, student lists, exhibition catalogs, newspapers and journals, letters, auction catalogs, advertisements, bankruptcy lists, the peerage, trade and street directories, dictionaries and encyclopedias, biographies, autobiographies and novels, business histories, product catalogs, court proceedings, medical records, parish registers, livery company documents, government records, maps, deeds, bank accounts, treatises and manuals, recipes, paintings, drawings, sculptures, photographs, pigment and canvas samples, and a wide range of products Roberson sold, from tiny paint cakes to life-size lay figures. I incorporated very little scientific analysis into my research, in part because of limitations on taking samples from much of the archival material, but also because Roberson’s accounts offered an abundance of detailed technical information about artists’ practices, and so my thesis concentrated on these documentary resources. I did, however, facilitate others’ analytical research while at the Hamilton Kerr Institute, providing samples for analysis of canvas grounds, millboards, adulterants in oil paints, and soap formation in grounds and paint layers.

As nineteenth-century works of art age to the point where they require repair, instrumental analysis is likely to play an increasingly prominent role in future research, both to inform conservation choices and to contribute to a more accurate picture of artists’ practices in a period of widespread technical change. The Roberson archive documents both the longevity of traditional materials and a substantial increase in the repertoire of new products available to artists, and it is not always possible to distinguish these by visual means alone. This makes analytical confirmation of the materials used in a specific work of art increasingly important, especially in suggesting how these materials are likely to respond to conservation treatment. In particular, the now-obsolete media that look, but do not behave, like oil paint that are recorded in the records of Roberson and other colourmen should alert conservators to the need to question their assumption that all paint is likely to be oil paint and to seek scientific verification that this is actually the case. Once the technical papers in Winsor & Newton’s extensive archive, also housed at the Hamilton Kerr Institute, have been explored, an even fuller picture of the complexity of nineteenth-century artistic practice is likely to emerge, helping to focus and guide instrumental analysis in order to corroborate, contradict, or challenge our expectations about what paintings were made of in nineteenth-century Britain.

Q: Through your affiliation with the Hamilton Kerr Institute you also have experience working with the forthcoming generation of conservators and researchers. In what ways has the field of technical art history evolved since you started your research career? Are there any instances where you still see room for improvement when it comes to integrating technical viewpoints into art historical research?

I should start by saying that interacting with students and interns at the Hamilton Kerr Institute and elsewhere has been one of the most interesting and engaging elements of my working life. Teaching always involves learning, and being able to encourage early-career conservators to undertake research of publishable quality has been consistently rewarding and informative. There are still positive changes to be made, but whenever I spend time with the next generation of conservators, I feel confident that the profession is in safe hands.

In terms of room for improvement, in 1990, after attending my first conservation conference, I asked my tutors why there appeared to be no Black conservators in Britain. Their response was that it was a very great pity but that “they simply don’t apply,” without, it seemed, very much curiosity as to why this was the case. Male and working-class conservators were also largely absent. This is something that has clearly changed very little in the intervening thirty-four years, and with severely limited funding for conservation training, poorly paid entry-level jobs, and the ongoing erosion of art education in the state sector, it seems unrealistic to expect this situation to alter for the better in the near term. This is obviously not just a conservation/technical art history issue, and so perhaps the most positive recent change is that the museum world is beginning to recognise that it needs to attract a representative workforce in order to serve a representative audience. So perhaps the days of conservation training being “a posh girls’ finishing school,” as it was once described to me, can really be put behind us.

Conferences are barometers of the field in other ways too, and conference programmes over the past three decades show a gradual shift from an emphasis on treatment and conservation case studies in favor of technical art history and technical examination. This is particularly noticeable in the papers presented at the UK’s Gerry Hedley Student Symposium as well as in the pages of the Hamilton Kerr Bulletin, which is unusual in publishing work by student conservators, and so this may suggest a similar shift in emphasis in the approach to conservation training. While it is clear that the novelty of seeing treatments presented as conference papers gradually lost its initial impact over time, the growing visibility of technical art history at conferences and in publications is perhaps also an indication of a maturing field becoming aware of how much more work there is to be done in understanding material complexity prior to formulating effective treatments. So, while our profession has recognised the value of understanding the materiality of works of art more fully, it is probably fair to say that this is not universally acknowledged in the wider art historical field.

It is easy, if lazy, to regard technical art history as little more than a subset of a subset (history—art history—technical art history), a discipline that exists to fill in the gaps and facilitate others in painting the broader picture. In some ways, our field has conceded to this perception by effectively talking amongst ourselves and publishing in journals that are not widely read outside our own field. However, the “material turn” and “thing theory” in the humanities and social sciences mean that our discipline’s long-established expertise in the materiality of art offers an opportunity to make a more significant contribution to a broader field of research in the future. I would therefore encourage conservators and technical art historians to widen their horizons and submit at least some of their research to publications outside the conservation and technical art history sphere. There are many publications that welcome papers with an art-technological approach, including those available online that have a worldwide reach. In my own research period, Victorian Studies at Indiana University, Nineteenth-Century Art Worldwide (available online), and the Journal of Victorian Culture from Oxford University Press are all well-respected, peer-reviewed journals with a broad readership and hospitable editors.

Q: During your recent fellowship with CRASSH, you described your book project The Starving Artist: The Romance and Reality of Suffering for Art in the Long, Hard Nineteenth Century as art historical analysis, coupled with social and cultural histories. Together, these methodological frameworks might be described collectively as social art history, within which artworks are regarded as a product of their sociocultural context. Do you think technical art history in particular has an important role to play in the social history of art? Are there any other methodological and/or art theoretical frameworks that you have come across in your research that correspond well with technical analysis as an investigative tool?

Martin Myrone’s 2020 book Making the Modern Artist: Culture, Class and Art-Educational Opportunities in Romantic Britain stated its intentions at the outset:

The aim here is a kind of “populated” art history, in which there is no art history without artists, as living, social beings, and in which no artwork can be detached from the conditions of its making including the socially conditioned agency of its maker if it is to be interpreted critically. There is no art history which is not also sociology.12

As a technical art historian I would add to Myrone’s list that there are also no artists without materials and no materials without manufacturers. There is no art history which is not also materiality.

Like Myrone, many art historians have been frustrated by their subject’s longstanding preoccupation with what have been identified as canonical works, key figures, and “isms” at the expense of a broader context for art history. In 1950, seventy years before Myrone’s publication, Ernst Gombrich’s The Story of Art opened with two succinct, subsequently celebrated sentences: “There really is no such thing as Art. There are only artists.”13 Gombrich, like Myrone, was also interested in the skills and processes of art, and within this broader theoretical approach, technical art history has much to contribute. The fields of conservation and technical art history have long been involved in fostering connections between the different disciplines within their compass—technical, scientific, art historical—and often see themselves as champions of interdisciplinarity. Therefore, combining the technical and social histories of art involves taking a step along an already familiar path and one that makes it possible, in the case of my starving artists, to reveal the richer materiality and more human story behind the work of art.

Prosopography, a methodology commonly used in history and social sciences, was a useful approach in trying to make sense of the data in almost 9,000 customer accounts in the Roberson archive.14 Anyone who has ever been faced with a collection of near-anonymous Smiths, Joneses, and Browns, and only slightly more distinguishable Johnsons, Clarks, and Whites will understand the challenges in trying to extract meaning from what, at first sight, seems a largely unrelated group of individuals. Although I was able to identify well over half of Roberson’s account holders, I needed to find a way to bring out their significance as a set or subsets, including those that remained largely anonymous. Prosopographical research is ideally suited to mass data of this type, with a proportion of obscure or unidentifiable individuals, aiming to investigate relationships, connections, and common characteristics within the group. In the case of Roberson, patterns emerged relating to their customers’ geography, social background, education, income, familial connections, and even parental expectations, despite the inconsistencies and omissions in the historical record. Importantly, for the purposes of technical art history, it was also possible to characterize common material choices in many cases, often influenced by gender, professional status, available finances, or social relationships. And despite there being many exceptions that could not be characterized as typical of any one subset, this prosopographical evaluation was useful in testing assumptions about artists’ technical choices, assessing art market fluctuations, evaluating changes in behavior or circumstance over time, and extracting an overview of what it meant to be an artist in nineteenth-century Britain.

Q: Having read the answers by your co-interviewee Jørgen, do you have any comments or reflections on his thoughts about technical art history as a research discipline?

Jørgen’s description of his influential and generous career highlights the interconnectedness within our field and reminds me of the opportunities it offered in the days when a newly qualified British conservator could work freely in Europe and observe at firsthand that things could be done differently, even better, elsewhere. While I worked in the Netherlands as an intern, at a very different level from Jørgen, our worlds overlapped: Ernst van de Wetering was my landlord; I worked on-site at the Museum Mesdag, benefited from the valuable input of the Central Lab’s staff, and looked on in wonder at the Deltaplan and a government willing to make such a large-scale investment in its national museums at a time when their British counterparts were still having to lobby their own government to abolish admission charges. From the outset, one of the strengths of technical art history as a discipline has been its international and collaborative nature, with an interchange of information and personnel that enriches all participants. The significant contribution Jørgen has made to technical art history, working across countries, championing a “without walls” approach to institutional cooperation, establishing Art Matters as an English-language open-access journal, and endorsing the importance of observational as well as analytical skills, exemplifies this international and collaborative approach and demonstrates its unambiguously positive impact. I hope that this is not something that is permanently lost to the next generation of student conservators and art historians coming of age in post-Brexit Britain, and that in future years they will once again be working alongside their European colleagues and mentors, learning to look and think, perhaps a little differently, and returning, with luck, with lifelong professional friendships, a satisfying research subject, and a chance to contribute to our evolving, expanding and rewarding discipline.

-

J. Wadum, “Christian IV’s Winter Room and Studiolo,” in RKD Studies: https://gersondenmark.rkdstudies.nl/4-christian-ivs-winter-room-and-studiolo-jørgen-wadum/[https://gersondenmark.rkdstudies.nl/4-christian-ivs-winter-room-and-studiolo-jørgen-wadum/](https://gersondenmark.rkdstudies.nl/4-christian-ivs-winter-room-and-studiolo-jørgen-wadum/) ↩︎

-

Deltaplan Cultuurbehoud: Onderdeel; plan van aanpak achterstanden musea, archieven, monumentenzorg, archeologie (Rijswijk: Ministerie van Welzijn, Volksgezondheid en Cultuur, 1990): https://catalogus.boekman.nl/pub/90-475B.pdf[https://catalogus.boekman.nl/pub/90-475B.pdf](https://catalogus.boekman.nl/pub/90-475B.pdf) ↩︎

-

CATS Publications: https://www.smk.dk/en/article/cats-publications/[https://www.smk.dk/en/article/cats-publications/](https://www.smk.dk/en/article/cats-publications/) ↩︎

-

See RKD – Netherlands Institute for Art History, “Marks on Art”: https://www.rkd.nl/en/current/ongoing-research/marks-on-art-painting[https://www.rkd.nl/en/current/ongoing-research/marks-on-art-painting](https://www.rkd.nl/en/current/ongoing-research/marks-on-art-painting) ↩︎

-

“TAH Interview: Jorgum Wadum, Keeper of Conservation, at the Statens Museum for Kunst in Copenhagen,” ARTECHNE – Technique in the Arts, 1500–1950 (Utrecht University): https://artechne.wp.hum.uu.nl/tah-interview-jorgen-wadum-keeper-of-conservation-at-the-statens-museum-for-kunst-in-copenhagen/[https://artechne.wp.hum.uu.nl/tah-interview-jorgen-wadum-keeper-of-conservation-at-the-statens-museum-for-kunst-in-copenhagen/](https://artechne.wp.hum.uu.nl/tah-interview-jorgen-wadum-keeper-of-conservation-at-the-statens-museum-for-kunst-in-copenhagen/) ↩︎

-

See Charlotte C. S. Rulkens et al., “'Exploring the Strengths and Limitations of Replication in the Humanities: Two Case Studies,” November 30, 2022 , Center for Open Science: https://www.cos.io/blog/exploring-the-strengths-and-limitations-of-replication-in-the-humanities[https://www.cos.io/blog/exploring-the-strengths-and-limitations-of-replication-in-the-humanities](https://www.cos.io/blog/exploring-the-strengths-and-limitations-of-replication-in-the-humanities) . A special issue on “Replication and Replicability” will soon appear in the online publication Humanities and Social Sciences Communications (HSSC). ↩︎

-

See Erma Hermens, “Technical Art History: An Interdisciplinary

Journey into the Making of Art” (2024): https://www.kressfoundation.org/getattachment/c85b7694-94dc-4c03-b23b-9e9f39720bc6/Hermens,-Technical-Art-History_2024.pdf?lang=en-US[https://www.kressfoundation.org/getattachment/c85b7694-94dc-4c03-b23b-9e9f39720bc6/Hermens,-Technical-Art-History_2024.pdf?lang=en-US](https://www.kressfoundation.org/getattachment/c85b7694-94dc-4c03-b23b-9e9f39720bc6/Hermens,-Technical-Art-History_2024.pdf?lang=en-US) ↩︎

-

Comite International d’Histoire de l’Art, http://www.ciha.org/[http://www.ciha.org/](http://www.ciha.org/) ↩︎

-

Comparative examples of labels are usefully provided online by Jacob Simon of the National Portrait Gallery in the “suppliers’’ marks” section at “Artists, Their Materials and Suppliers”: https://www.npg.org.uk/collections/research/programmes/artists-their-materials-and-suppliers/ ↩︎

-

UK probate records can be sourced at https://probatesearch.service.gov.uk/. ↩︎

-

Sally Woodcock, “The Golden Age of the Living Painter, 1860–1914? How Debt, Default and London’s Declining Art Market Affected Painters in the Second Half of the Nineteenth Century,” in Expression and Sensibility: Art Technological Sources at the Rise of Modernity, ed. Christoph Krekel, Joyce H. Townsend, Sigrid Eyb-Green, Jo Kirby, and Kathrin Pilz (London: Archetype, 2017), 8–15. ↩︎

-

Martin Myrone, Making the Modern Artist: Culture, Class and Art-Educational Opportunities in Romantic Britain (New Haven: Yale University Press, distributed for the Paul Mellon Centre for Studies in British Art, 2020), 2. ↩︎

-

Ernst H. Gombrich, The Story of Art (Oxford: Phaidon,1950), 15. ↩︎

-

Prosopography involves the study of prosopographies, the descriptions of a person’s social and familial connections. ↩︎